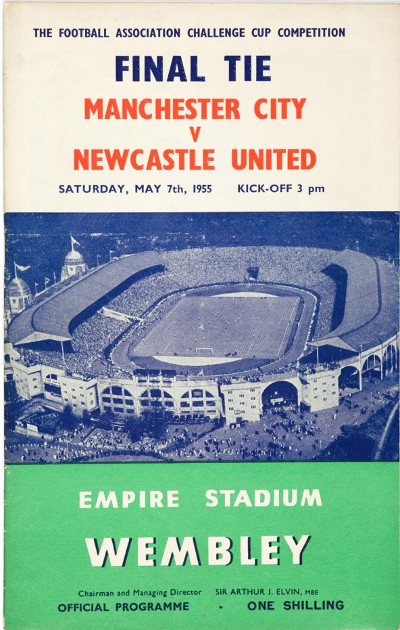

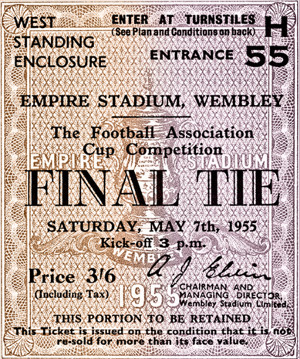

Wembley Stadium, Saturday 7th May 1955

NEWCASTLE UNITED 3 MANCHESTER CITY 1

It could have been the happiest day of the young man's life.

He was twenty-four, a superb physical specimen, and he had just made his

international debut, in an England team which had crushed the Scots 7-2. He

had come a long way from a humble start as a Southport winger: now he was

Manchester City's right-back, seemingly booked for a long run in his

country's colours, and he was playing in the Cup Final.

But suddenly the gold turned to ashes.

After twenty minutes, the young man's studs caught in the holding turf of

Wembley as he tried to make a quick turn. He went down in agony, knee

ligaments so severely damaged that he could take no further part in the

match and no further active part in football. The career of Jimmy Meadows

ended as a result of that injury, the most cruel blow of the many struck by

the Cup Final hoodoo.

Would City have won with a full team? The argument is endless, but I very much doubt it. Even before Meadows went off, they were struggling, a goal down, indebted to magnificent goalkeeping that the margin was no greater. Newcastle, drawing on their vast Wembley experience, were dictating the play, confident that victory was well within their capabilities. Once Meadows had gone, that victory became assured. True, City found previously unseen depths of skill and spirit to keep in the hunt for an hour, but Newcastle won, in the end, at walking pace. As in 1952 much of the glory was removed because fate had given them a numerical advantage, but this was their third Final victory in five years, a notable achievement by any criterion.

It was also the most remarkable of the three, achieved against a background of argument and contention. The club had appointed a manager, Dugald Livingstone, but there were many stories of upsets between him and the board. The North-East was divided over the case of Frank Brennan, who sought a transfer and ultimately left under something of a cloud. And injuries hit so many players during the season that seventeen were called on during the Cup run, the most by any victorious club since the war.

True, Milburn remained, but he now figured on the wing or at inside-forward, his days of inspiring leadership seemingly done. Ivor Broadis, an England international inside-right signed from Manchester City, had supporters alternately in ecstasy and despair as his form swung unpredictably. Replaced by another international, Reg Davies, Broadis did not regain his place when injury kept the Welshman out of the Final. Milburn, chosen for the wing, moved inside, and Len White came in.

Beset by these varying troubles, Newcastle reeled to Wembley, aided by far more good fortune than they had the right to expect. But if the latest wearers of the black and white stripes lacked the class of earlier teams, they had even greater tenacity, and their hard work paid in the end. At Wembley, throwing off all uncertainty, they played extremely well, inspired by the efforts of two men. One, Bobby Mitchell, was taking part in his third Final, at the end of his finest season. Even when others struggled, Mitchell shone, adding a practical touch to his inherent ball-playing skill: his goal at Wembley was his twentythird of the season. His fellow Scot, Jimmy Scoular, provided much of his ammunition. Scoular, as forceful a captain as Joe Harvey, whom he had succeeded, was a controversial figure for some fifteen years. He won two championship medals with Portsmouth, thirteen caps, and even at the end of his career, with Bradford, he was as awesome an opponent as ever. Powered by legs like oak trees, Scoular gained a reputation for toughness. He was sometimes the victim of unscrupulous opponents and officious referees, though the fact that he was sent off the field four times indicates that he was not always on the receiving end.

Goalkeeper Ronnie Simpson, playing in his second Final, was the third Scot in the Newcastle team, while Irish international left-half Tom Casey was one of seven newcomers to Wembley. Scoular and White, whose brother Jack captained Southern Section champions Bristol City that season, were also without Final experience, as were left-back Ron Batty, centre-half Bob Stokoe, and the remaining forwards, Vic Keeble and George Hannah.

Keeble, from Colchester, was no Milburn, but he had a heavyweight's heart. Hannah, a Liverpudlian signed from Linfield, was a delightful ball-player who later joined the club he helped to beat at Wembley. He had been in the reserves at the time of the 1951 and 1952 Cup victories: so too had Stokoe and Batty, two "home-grown" products at last gaining reward for years of loyal service. Two other long-serving locals with better fortune were Milburn and Bobby Cowell, who joined Mitchell in their third Final. But Cowell's luck was soon to run out. He was hurt on his club's close-season tour of Germany, and like Meadows, his rival right-back at Wembley, did not play again.

A goal by Keeble enabled Newcastle to win their first Cup-tie of the season, against poor Second Division opposition at Plymouth. In the fourth round they again had a single goal to spare, defeating Third Division Brentford 3-2 on Tyneside. In the fifth they drew twice with Nottingham Forest, a mediocre team from Division Two, saving themselves on both occasions with late goals. By mutual agreement the clubs tossed to decide the venue of the second replay, instead of going to a neutral ground. Newcastle won both the toss and the tie, scraping through 2-1 after extra time on their own pitch, to qualify for a match with Huddersfield. Here again they escaped by scoring with time almost up - the goal came from Yorkshireman White, who later joined Huddersfield - and in the replay Newcastle pulled through 2-0.

This entitled them to meet York City, who merit a chapter to themselves if a book about giant-killers is ever written. In February 1954 York sold centre-forward David Dunmore to Spurs, and spent the money on several new players. Manager Jimmy McCormick, a former Spurs winger, resigned in the following September, but the men he had bought formed the nucleus of a team which was to astound the football world by going further in the Cup than any Third Division club had gone before.

York's victims included Blackpool, Matthews and all, and another team to fall to them, by a twist of fate, was Tottenham. Dunmore, dropped to twelfth man, watched from the touchline as the team his transfer fee had helped to build raced to a 3-1 victory. With the country afflicted by a newspaper strike, York's performance in the semi-final was not as widely appreciated as it deserved to be. They took the lead through Arthur Bottom, who scored thirty-eight times during the season and so impressed Newcastle that they later signed him. Once in front, York held on so grimly that all Newcastle's efforts failed save one, when Keeble equalized. From Hillsborough the teams moved to Sunderland for the replay, where White gave United an early lead. When centre-half Alan Stewart cut his head and moved to the wing, York seemed finished, but Stewart - a native of Newcastle - made an excellent forward, and the reshuffled side fought with such skill and vigour that they had a chance of an equalizer right up to the last minute. Then Keeble claimed yet another valuable goal, and so ensured his club's appearance in their tenth Final, a record still unequalled. Sadly there was no consolation for York, who were also in the running for promotion. Their Cup run caused such a pile-up of fixtures that they had to play six games in ten days, and they could only finish fourth.

Newcastle had met only one other First Division team, Huddersfield, on the way to Wembley, but their five ties had stretched to nine matches, on at least four occasions they had been lucky to escape defeat, and as many as eight different forward formations had been tried. Their struggles were in keeping with the competition as a whole, for replays were ten a penny. Stoke's tie with Bury in the third round and the Doncaster-Villa meeting in the fourth both went to five matches.

In contrast, Manchester City had won every tie at the first attempt, although their opponents included Sunderland (fourth in Division One), Manchester United (fifth), and Birmingham and Luton, who both came up from Division Two. Not one of the four managed to score against City's defence, and the only goal the Lancashire club conceded was in round three, when Derby, later relegated to the Third Division, were beaten 3-1. The scorer was Jesse Pye, who had netted twice for Wolves in the 1949 Final.

City's defence was more impressive in Cup-ties than in League matches, but the club still finished seventh, and earned deserved reward for their courage in experimenting with the method popularly known as the Revie Plan, in which the deep centreforward acted as the midfield link, leaving the inside men as strikers. Revie, so unluckily kept out of Leicester's Cup Final six years earlier, could not have been bettered as the fulcrum of manager Leslie McDowall's new style. Tall but lithe, he was not handicapped by weight in his endless journeyings round the pitch, and his adroit distribution was the starting-point of many of his team's attacks. During the season Revie attracted enormous publicity, reached the England team, and was chosen Footballer of the Year.

His part in City's success could hardly be over-estimated, but this was far from a one-man team. Right-half Ken Barnes, of similar build to Revie, was not far removed in skill: if the one was unlucky to gain only six England caps, the other was even more unfortunate not to gain one. While these two operated mainly in midfield, left-half Roy Paul lay back to act as a shield for the centre-half, Dave Ewing. Paul, captain and Welsh international, had returned from an ill-fated trip to Bogota, that so-called Eldorado, to make his peace and prove himself one of the best wing-halves in the game. With Ewing virtually unbeatable in the air, if sometimes shaky on the ground, and Paul, Meadows and the consistent Roy Little, at left-back, City's defence could be very good on its day.

All defences need a goalkeeper, and City had the best available in Bert Trautmann, the big blond from Bremen. I first saw Trautmann playing for St. Helens, the town in which he had settled after years as a prisoner of war following service as a paratrooper. The memory of that rainy evening on that cramped little ground stays with me still: Trautmann was superb by any standards, and I take some sort of pride in having "discovered" him, long before he became famous. In due course City signed him, and after both club and player had endured the taunts of bigots with minds full of hate and empty of forgiveness, Trautmann duly became Manchester's favourite adopted son. Perhaps my early sight of him colours my view, but I still think the German is the best goalkeeper I have seen.

Trautmann, Barnes, Paul and Revie were all first-rate performers, and City had a fifth in Bobby Johnstone, a "sixpennypiece dribbler" and one of the finest inside-forwards to come off the seemingly endless Scottish supply line. Often the target of English clubs, Johnstone waited a long time before leaving Hibernian. He timed the move exceptionally well, appearing in the Final after only nine previous games for his new club. Soon after his move he and Revie were the opposing inside-rights in the England-Scotland match, when Meadows made his debut.

Johnstone's arrival was opportune for club as well as player, for three days after his signing inside-left Johnny Hart broke a leg. And another blow fell just before Wembley, when Welsh winger Roy Clarke was injured. Another international, Irishman Fionan Fagan, switched to the left, with Bill Spurdle coming in on the right to partner Joe Hayes. Fagan, like Revie, had been recruited from Hull: Spurdle, formerly with Oldham, was the first native of the Channel Islands to play in a Final, and Hayes had been picked up from under the nose of his local club, Bolton. All three were useful rather than brilliant, although Hayes scored a lot of goals in a long career.

Cup Final day was typically warm and sunny, with an immediate surprise as the teams walked out. Newcastle were ready for action, but City emerged in sky-blue track suits over shortsleeved Jerseys with V necks, shorts shorter than average, and the latest German boots. Innovators in tactics, City were also ahead of the pack in equipment.

But from the start this wasn't City's day. In the first minute White forced a corner off Little and lofted the kick into the middle for Milburn, all alone, to jump and head a simple goal through a statuesque defence. Although they had used the track suits to keep warm, City had been caught "cold" and unprepared.

Soon Meadows was down, almost on the spot where Barnes had been hurt in 1952, and again in an attempted tackle on the elusive Mitchell. Now more than ever depended on Revie and Barnes, who lacked nothing in their efforts to force an opening, while Fagan was full of fire as he roamed from wing to wing, trying to do his own job and that of Spurdle, who had gone to right-back. But City's defence was vulnerable, and only Trautmann kept them in with a chance in the first half. He flung himself at a ferocious shot from White, passing far to his left, to make a magnificent save, holding the ball when most goalkeepers would have settled for touching it. Then, when Keeble caught a cross square on his forehead while standing inside the goal area, Trautmann somehow reached the ball, knocked it down, bounced up and plunged again to smother it at the centreforward's foot.

Faced by such a goalkeeper, Newcastle must have wondered how they had beaten him once, and how they could do so again. As they faltered, so City grabbed at the chance, with Johnstone turning on one of the sudden bursts which made him so dangerous. He put both Fagan and Hayes through for shots which failed narrowly. Then he ghosted past four men in ten yards, only for Simpson's legs to stop his shot and deprive him of a superb goal. Still Johnstone kept his inspiration, and when Hayes crossed from the right, the little Scot launched himself head-first at the ball, to butt it wide of the goalkeeper's left hand. City were level, and almost at once the half-time whistle sounded.

Judging by the way City were fighting, anything seemed possible. But Newcastle soon showed that hope was founded on fantasy. Scoular was the man who gave his revived team their grip, moving the ball far and wide, across the field and even backward as well as forward, so that City's depleted forces had to chase and chase again. At Wembley, against ten men, possession is everything. Newcastle kept the ball, and moved it neatly from man to man with commendable calm, and waited for fatigue to open the gaps.

One came in the fifty-second minute, and Scoular spotted it. His cross-field pass fell deep behind the defence, to leave Mitchell clear. He was acutely angled and a centre seemed his only move, but as Trautmann dived outwards in anticipation, so Mitchell hit the ball hard and straight through the narrow gap behind the goalkeeper. Seven minutes later, as City struggled towards the surface, Newcastle pushed them under, for the last time. Again Scoular put Mitchell clear, and although Trautmann parried the shot, Hannah hit the rebound first time, with violence out of character for so delicate a craftsman, through a crowded penalty area and into the net.

All was over as far as the result was

concerned. The last halfhour was miserable anti-climax, with City spent

and Newcastle charitably disinclined to seek too hard for further goals.

Scoular dominated in midfield, and Mitchell did much as he pleased against

poor Spurdle. Revie still roamed and Fagan still chased everything there was

to chase, but the game was dead long before referee Leafe blew for the last

time.

By then, Meadows was sitting at the touchline, bathed and dressed, his world

in pieces. And the demand for substitutes was already homing in on Fleet

Street.

David Prole from Cup Final Story

1946-1965

Manchester City: Trautmann, Meadows, Little, Barnes, Firing, Paul,

Spurdle, Hayes, Revie, Johnstone, Fagan.

Referee: R.Leafe of Nottingham.

Goals:

MCFC: Johnstone 45 NUFC: Milburn 1, Mitchell 52, Hannah 59

Crowd: 100,000