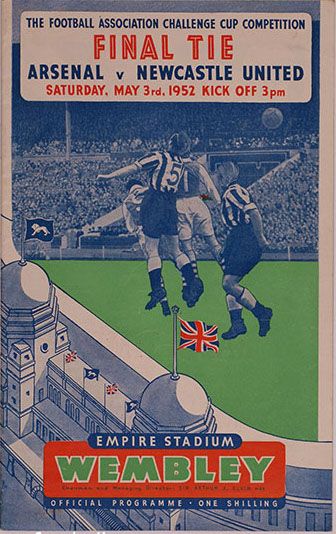

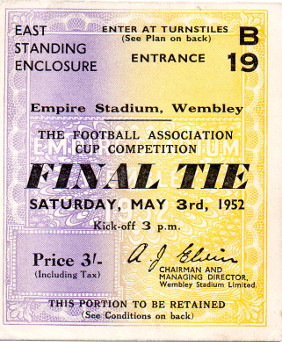

Wembley Stadium, Saturday 3rd May 1952

ARSENAL 0 NEWCASTLE UNITED 1

Arsenal's finest hour came, ironically,

in defeat.

The most famous club in football, the club which had known success after

success for a quarter of a century, had to lose before gaining wholehearted

acclaim. Always there had been detractors, purveyors of the old cry of

"lucky Arsenal". But after the 1952 Cup Final, Arsenal had nothing

but friends.

With twenty-two minutes gone, Wally Barnes injured a knee. He played on with his leg strapped, broke down in another tackle, and went off. He returned, but almost at once fell in agony after colliding with the flag at the half-way line, and was taken to the dressing room. Damaged ligaments, which kept him out of football for more than a year, forced Arsenal to play for over half the game with ten men. Not ten fit men, either. Three of them, Jimmy Logie, Ray Daniel and Doug Lishman, had come almost direct from hospital to the Stadium - Logie after internal haemorrhage, Daniel after breaking a wrist, Lishman after a cut had turned septic.

The injury to Barnes was the final blow in a crippling run of injuries which had wrecked Arsenal's hopes of becoming the first modern team to achieve the Cup and League double. Their championship chance faded to the accompaniment of breaking bones and tearing muscles, and they went to Wembley to face Newcastle, defending the trophy, determined to become the first team to win it in successive seasons since Blackburn in 1890 and 1891. Although they were only eighth in the League, Newcastle's total of ninety-eight goals equalled the highest recorded in the First Division since the war. They had added fourteen in the Cup, and in contrast to their troubled opponents had fielded the same eleven men throughout the competition.

This was the size of Arsenal's task. Not surprisingly, they were beaten. But they restricted Newcastle to one goal. With only six minutes left. And in off a post, too. No wonder the Newcastle director-manager, Stan Seymour - himself a scorer in a Wembley Final, in 1924 - paid generous tribute. "We have won the Cup, but the glory is yours," he said. The most avid supporter could not help but agree.

There was glory galore for the Gunners on that rainy day. Particularly for Daniel, for Lionel Smith, the English international left-back, for Alex Forbes and Freddie Cox. And, most of all, Joe Mercer. At thirty-eight, Mercer spared himself nothing. Those large feet, on those curiously warped legs, must have made their impression on every blade of grass on Wembley's large, energy-sapping pitch. He cajoled, he urged, he waved his arms, he clapped his hands. He ran and tackled and passed. He fell and rose again, a human machine seemingly incapable of failure. Even when the goal came Mercer refused to give up. Only at the last whistle did his shoulders droop in despair. Soccer history has few greater examples of selfless devotion to a cause: it was enough to bring a lump to the throat.

Arsenal's failure to win either League or Cup that season was tragedy. Success in one would have been remarkable, success in both a football miracle. Tottenham achieved the double in 1960-61, with a better team, but their luck was in throughout he season. Arsenal, in that earlier era, went desperately close to their twin target in spite of some catastrophic misfortunes. Only goalkeeper George Swindin played in every match in a season comprising fifty-one games. lnjuries affected all the others in turn, while there were representative calls on the many internationals, and every team brought extra effort to their game in a bid to beat Arsenal, the club everybody loves to hate. Yet in spite of all these obstacles, the Gunners stayed in the race until the last stride. Only a very good Manchester United side could deprive them of the championship (although Spurs snatched second place on goal average at the last gasp), and the Barnes injury prevented a possible consolation in the Final.

Arsenal had one three-month spell without defeat - their seventeen matches included eight in three weeks - without being able to hold Manchester United. The teams met in the last League game of the season, and Arsenal had to win by at least 7-0 to take the title on decimals. They had already sent a congratulatory telegram to Old Trafford, but even then fate did not relent: they lost 6-1 - their heaviest defeat for six years - after being reduced to nine men.

In the week before Wembley, Highbury resembled an ambulance station more than a football ground. The team as a whole was weary, several members were nursing minor damage, Logie was in bed, Lishman had just left his, and Daniel was experimenting with a lightweight shield over his injured arm. He received permission to play from both the F.A. and Newcastle - which was just as well for Arsenal: his deputy, Arthur Shaw, had broken a wrist at Manchester, and the third-string centre-half, Jim Fotheringham, had damaged his spine on the same day. Lishman and seven others were as fit as could be expected after all they had been through. Logie declared himself available, although he must surely have been left out of any other game bar this, so manager Tom Whittaker's problems were whittled down to one. His centre-forward choice had fluctuated all season, between Reg Lewis, Peter Goring and Cliff Holton. In the end the manager chose Holton, gambling on his strength and shooting power. Sadly, Holton did not come off, and in retrospect at least it seems that the experienced Lewis, who had with scored eleven goals in twelve games during the season, and had netted twice in the 1950 Final, would have been a wiser selection than a 23-year-old playing his first Cup-tie.

Mercer, Swindin, Barnes, Forbes, Cox and Logie remained of the 1950 team. Barnes had gone to right-back on Scott's departure for Crystal Palace, and Daniel had supplanted Leslie Compton. The pair had been on opposing sides on the day Daniel won his first Welsh cap, while still an Arsenal reserve, the previous season. The team was completed by the left-wing pairing of Lishman - who had recovered from a broken leg and was to be his club's leading scorer for five successive seasons - and Don Roper, a powerful raider who lacked the consistency which could have taken him into the top flight.

What luck Arsenal had during their Cup run came in the draw, which pitted them against four clubs from lower divisions. Norwich, Barnsley and Leyton Orient were beaten with an aggregate score of 12-0, although the first and third matches were away, but Arsenal had a fright at Luton before winning 3-2. The man who pulled them through was Cox, back on the right after losing his place to Arthur Milton, a youngster chosen for England after only twelve League games. Cox came in again on Milton's failure to maintain his early form, and two goals at Luton proved his right to return.

Cox was far from finished. In the semi-final Arsenal were drawn to meet Chelsea, in a repeat of their 1950 clash at the same stage. The match was postponed for a week because of snow - the first time a semi-final had been so affected - but the delay did not bother Cox: he scored in a 1-1 draw, and added two more in the replay. In three seasons he had hit only seven League goals, but in the same period had scored seven in Cup-ties, five of them against Chelsea on the ground where he had been so unmercifully barracked while a Tottenham player.

Apart from Luton and the first Chelsea match, Arsenal had had as simple a passage as any team could reasonably expect. It was a different story with Newcastle, who were in trouble nearly all the way. In the third round they were 2-1 down with ten minutes left - both Aston Villa goals were scored by Johnny Dixon, a Geordie - before a whirlwind rally took them to a 4-2 victory. In round five Newcastle were lucky to defeat Swansea 1-0, and in the sixth only a superb hat-trick by Milburn took them through 4-2 at Portsmouth. These were the only goals Milburn scored in the competition that season, but every one was a gem, obtained in spite of opposition from Jack Froggatt, the reigning England centre-half. The only tie United won with much to spare was in the fourth round at Tottenham, when the) beat the champions 3-0. Added to a 7-2 League victory at home a few months earlier, this game completed revenge for that 7-0 rout the previous term.

While two London clubs met in one semi?final, Newcastle faced the challenge of Blackburn Rovers in the other. The famous Lancashire team had made a brave recovery from a dreadful start - only six points from their first sixteen games - and were the only survivors of the unusually high total of nine Second and Third Division clubs to reach the fifth round. Their speed into the tackle frustrated all Newcastle's attacks, none doing better than the future England captain, Ronnie Clayton (then only seventeen) and Ron Suart, who had missed Blackpool's 1948 Final through injury. The replay followed a similar pattern, and although Robledo put Newcastle ahead, Blackburn levelled and looked set for extra time until a handling offence gave Mitchell the chance to convert a penalty.

Mitchell was one of seven men who duly lined up for their second successive Final. The others were Cowell, Harvey, Brennan, Walker, Milburn and Robledo, the latter being joined in the team by his younger brother, Ted, who had taken over from Crowe at left-half. George had a fine season, his thirty-nine goals in League and Cup making him the First Division's top scorer and setting a post-war club record which still stands.

Newcastle's team was one of the most cosmopolitan to appear in a Final, comprising four Englishmen, three Scots, two Chileans, a Welshman and an Irishman. Mitchell, Brennan and former amateur international Ronnie Simpson were the Scots - Simpson had replaced goalkeeper Fairbrother after he had been injured early in the season - while the Irishman was Alf McMichael, at left-back for Corbett, and the Welshman was inside-right Billy Foulkes, formerly of Chester. Ten days after his transfer Foulkes scored against England with his first kick in his first international, and six months later he collected a Cup medal.

If Foulkes was the luckiest man on the pitch at Wembley, his compatriot, Barnes, was the most unfortunate. Captain of his country's team, which shared the international championship and beat the Rest of the United Kingdom in the Welsh F.A. Centenary match, Barnes had played in fifty-two competitive games during the season and missed only one. A full-back of admirable skill and composure, he was one of the men Arsenal could least afford to lose.

Up to the time they lost him, Arsenal had been as good as their opponents. If Lishman's overhead kick had gone in, instead of scraping a post, they would have had the flying start so invaluable in a big game. Only two minutes had passed, and the blow to Newcastle's morale might have been irreparable. But it was not to be. All too soon came the sad exit of Barnes the first of the ten-year sequence of Cup Final injuries - and the sight of the reshuffled team trying to cope with that formidable Newcastle attack. Yet Mercer and company fought so well in spite of their handicap that they stayed in the game with a chance of victory, albeit a slight one, until the last few moments.

Mercer was outstanding, with Forbes a tremendous worker and Smith playing Walker out of the match. Roper, who knew a lot about the wingman's art, made an excellent deputy full-back, so that even the elusive Mitchell found himself frustrated. And Daniel, injured arm and all, put on a brilliant display at centre-half, keeping Milburn in subjection much as Brennan had done to Mortensen a year before. Daniel's positional skill and impeccable coolness, allied to the cover of the entire defence, meant that Swindin was without employment for long spells, even though much of the play took place within dangerous distance of his goal.

Yet Milburn was twice within an ace of scoring, taking half-chances with the speed that made him so dangerous. First he thumped a left-foot shot a matter of inches past a post. Then he flicked a back-header wide of the goalkeeper, only for Smith, craning a long neck, to nod the ball out from under the bar. Newcastle needed more of Milburn's positive touch in the penalty area, for Walker and Foulkes failed with reasonable chances, and Robledo had mislaid his scoring form. As the minutes passed and Arsenal, incredibly, still held on, the possibility also remained of a breakaway goal. It was a faint hope, for Holton was out of his depth and Logie was spent long before the end. With Roper withdrawn into defence, Arsenal's attack was virtually a two-man affair. Lishman and Cox toiled with valiant energy - particularly Cox, who appeared in all sorts of positions in an attempt to do the work of three men. Brennan and his colleagues were rarely troubled . . . yet the hope lingered.

In the last quarter Arsenal's plight was pitiful. Men took longer to regain their feet after falling, and muscles must have ached without relief as the siege continued. But still Mercer and his men struggled on: even when Mitchell feinted his way past three challenges in six yards, yet another red and white jersey was in the way of his final shot.

With eleven minutes left, Arsenal almost achieved the impossible. Cox, with still another solo effort, forced a corner, and Lishman's was the head to connect with his kick. Simpson was beaten, but the ball caught the top of the bar and passed over. Five minutes later the bounce went the other way, as fate's last malignant blow. Mitchell, who had become more and more the victim of his own mistrust, suddenly produced a typical piece of sleight-of-foot to round Roper, and George Robledo beat Smith in the air to head the centre down, past Swindin's left hand, and over the line off the base of the post. Arsenal had capitulated at last, significantly when Roper was still on the ground after his failed tackle and Logie was prone at the other end. It was tragic, this blow, in its finality, yet it was also a relief, sparing Arsenal from the further agony of extra time and the possibility of a heavier defeat.

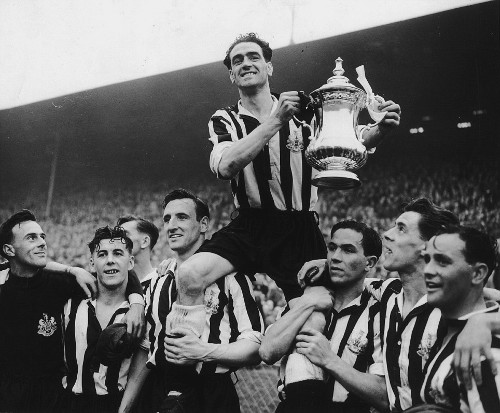

For the second time in twelve months Harvey was chaired from the field with the Cup in his possession. He was congratulated by Mercer - who had been his sergeant-major for a time during the war - and then ran off, displaying the trophy in the manner of all winning leaders. But the cheering had a shame-faced faced air about it: the bauble was Newcastle's, yet the glory was with the losers.

Arsenal dragged themselves up the staircase to receive their medals, and then straggled down again in attitudes of pitiful dejection. But they were to have the last word, in true fashion. At Mercer's instruction, they somehow found the strength to run to the dressing room.

David Prole from Cup Final Story

1946-1965

Arsenal: Swindin, Barnes, Smith, Forbes, Daniel, Mercer, Cox, Logie,

Holton, Lishman, Roper.

Referee: A. Ellis of Halifax.

Goal: G.Robledo 84

Crowd: 100,000