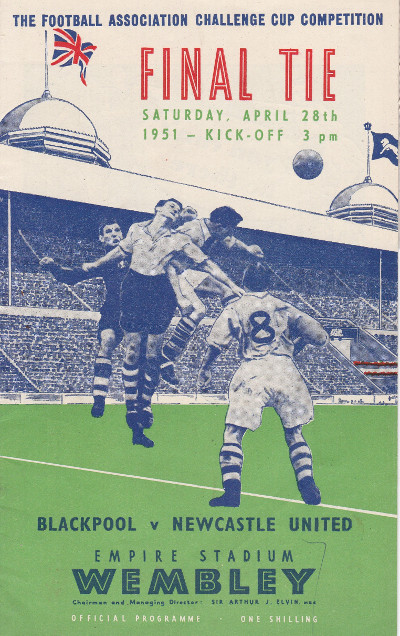

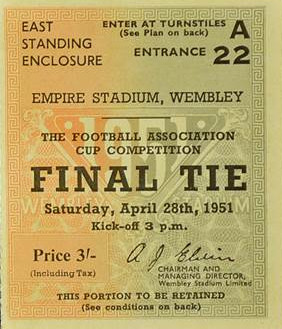

Wembley Stadium, Saturday 28th April 1951

BLACKPOOL 0 NEWCASTLE UNITED 2

Milburn's match: his goals have gone into history, ranking with the most spectacular Wembley has seen. It was a triumph for the popular hero, the player who might have stepped from the pages of the comics we devoured so eagerly in our youth. Milburn, a player of startling speed and furious shot, was the match-winner supreme. Football has had few sights to compare with that of Newcastle's idol in full stride. Originally a winger, "Wor Jackie" became famous as a centre-forward of the old "shoot on sight" school. I wonder how he would fare today, when defences at times of danger resemble Oxford Circus in the rush hour. No doubt his output of goals would be less, but he would still create plenty of excitement.

Milburn is the name which springs to mind when the memory of Newcastle in the fifties is evoked, for he was the essence of the speed and skill the famous Tyneside club brought to their matches at that period. Capped thirteen times (and only twice on the losing side), he remains one of the best strikers England have had since the war, but it is as a Cup-hunter that he is best remembered. He and Stanley Mortensen of Blackpool were similar in many ways, perhaps too similar for fate to favour both when they were on opposite sides in the Final. The luck went Milburn's way, while Mortensen knew only disappointment.

Newcastle have long been renowned as Cup-fighters. The memory of their earlier giants lived on through the thirties, a source of comfort for their supporters as the club slid into the Second Division. They could look back to the golden age between 1905 and 1911, when Newcastle reached the Final five times, even though the old Crystal Palace ground had a stultifying effect: United were beaten there on four occasions, and on the fifth had to go to Everton for a replay before winning the trophy. But if the Palace brought disaster, Wembley brought triumph, for Newcastle have won there on each of their five appearances - in 1924, when two late goals wrecked Aston Villa, in 1931, the year of the historic "over the line" goal, and in 1951, 1952 and 1955.

Milburn went into history a few seconds after four o'clock on the sunlit afternoon of April 28, 1951, with his first goal. Four minutes later he underlined his name with a second. Both were remarkable efforts, fit to win any match, and although the scorer played in two more Cup-winning teams, these were his greatest moments. The Stadium has seen few greater.

This match ended with victory going to the better side. Yet as in 1948 there was a touch of sadness about it, for Stanley Matthews was again deprived of the medal he wanted. Matthews was still delighting us on Blackpool's right wing, a little more prone to injury but still the same, incomparable. People wanted Blackpool to win for his sake: after the match they shook their heads and said "Poor old Stan" - not knowing that he was yet to surprise us all.

Matthews and Mortensen were two of the six survivors of the Blackpool team beaten by Manchester United. Shimwell was another, rugged as ever, his one England cap now behind him. Johnston, Footballer of the Year, was another, and the other half-backs, Hayward and Kelly, made up the sextet. The new comers were George Farm in goal, Tom Garrett at left-back, Jackie Mudie at inside-right, and Bill Slater and Bill Perry on the left wing. Farm, signed by manager Joe Smith when in Hibernian's reserves, had an unusual method of catching the ball, with one hand under it and one on top. He was far from infallible, but he was good enough to play more than 400 games for his club, and ten for Scotland. Little Mudie, in his first full season, was a hard worker with an eye for goals, who went on to win seventeen Scottish caps, in all three inside-forward places. Garrett, from Durham, and Perry, a South African of English extraction, both played three times for England: Perry was recommended to Blackpool by Billy Butler, who had been a colleague of Smith's in two Bolton teams at Wembley. Slater, an amateur international, had had only a handful of League games and had not been in the first team for six months prior to appearing at Wembley as deputy for the injured Allan Brown. The risk did not pay, but Slater had belated consolation in 1960, when he led Wolves to a Final victory and was also chosen Footballer of the Year. He had then moved to half-back, and had gained several full caps to add to his amateur honours.

Slater was one possible weakness. Another was the decline in speed of the veteran Hayward, the only one of the eleven fielded at Wembley who was not a current or future international. And the forwards, not unnaturally, relied enormously on Matthews, chance-maker supreme, and Mortensen, who had scored thirty League goals during the season-the best total of his career-plus five in Cup-ties. The task of subduing these two had been beyond all the clubs Blackpool met on the way to Wembley. Charlton were held 2-2 and beaten 3-0 in the replay, Stockport - who included George Dick, Blackpool's 1948 inside-left-went down 2-1, Mansfield fell 2-0, and a penalty by Brown disposed of Fulham, paving the way for a semi-final with Birmingham.

The Midland club might well have had consolation for narrowly missing promotion from the Second Division by going to Wembley. They were unlucky not to win against Blackpool at Maine Road, in a match which finished without a goal, and they almost pulled back to equality in the replay at Goodison Park after being two down. So, as in 1946, Birmingham fought to within one stage of Wembley without getting there, and once again two First Division clubs were left after the chances of an outsider reaching the Final had looked bright: twelve of the third round ties were won by teams from a lower division than their opponents.

While enjoying Cup success, Blackpool also put up a good show in the League and won talent money by finishing third, six points behind Manchester United and ten behind Tottenham, who swept to the championship with their glorious push-and run style. Newcastle were fourth, having been fourth and fifth in the two previous seasons after their promotion in 1948. They were too inconsistent to be really serious contenders for the title, but their workmanlike defence and powerful attack made them good prospects for the Cup - which, after all, can be won by six good displays spread over four months.

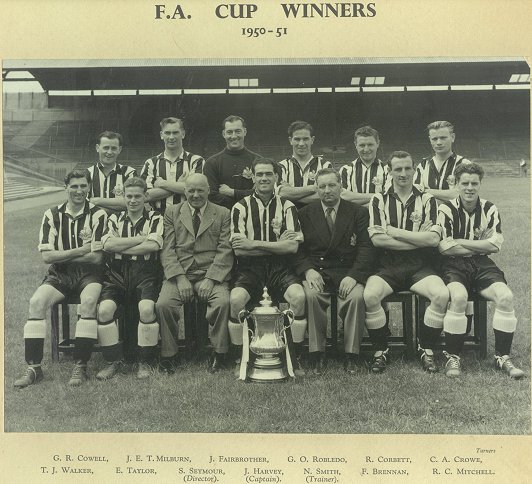

Milburn scored in the first three ties, with Bury beaten 4-1, Bolton 3-2 before a crowd of 67,559, still the post-war record for St. James's Park, and Stoke 4-2. But Bristol Rovers caused one of the year's many surprises by forcing a goalless draw on Tyneside in the sixth round, and then took the lead on their own ground. This shock gave Newcastle the chance to demonstrate one of their outstanding virtues, the ability to turn a match inside out with a quick burst of scoring. Three goals came in ten minutes, to shatter the Bristol dream of becoming only the second club from Division Three to reach the semi-final. Instead, Newcastle went through, to produce two goals in thirty seconds and turn the tables on Wolves after Stanley Cullis's team had looked set for Wembley by going in front in the replay. The first match, like Blackpool's, had been goalless: this was the first time both semi-finals had not contained a score since 1912. Newcastle's replay marksmen were Milburn and Bobby Mitchell, the lanky Scot at outside-left. On his day Mitchell was almost as great a match-winner as his colleague, and although he could be irritatingly prone to trying too much on his own, United fans always lived in hope of great deeds when he was in possession.

The other winger, Tommy Walker, had a curious career. Often supplanted by one of the many costly signings the club made, he usually managed to get back into the team, unspectacular where Mitchell was all fireworks. Walker made an admirable partner for Ernie Taylor, one of the smallest men in soccer history, whose ball control and quick brain helped him to Wembley with three different clubs. Worse forwards than Taylor won more England caps than he did: his one match for his country was against the Hungarians in 1953, when his was not the only international career to come to a summary conclusion. Tiny Taylor was in marked contrast to the inside-left, George Robledo, of the bulging thighs and glossy hair. Robledo, son of a Chilean father and a Yorkshire mother, played for Chile against England in the 1950 World Cup, and joined Newcastle from Barnsley. United have struck few better bargains.

The Newcastle defence comprised Jack Fairbrother in goal, local-born backs in Bobby Cowell and Bobby Corbett, Scottish international Frank Brennan at centre-half, an inspiring skipper in Yorkshireman Joe Harvey at right-half, and another local, Charlie Crowe, on the other flank. Apart from Fairbrother, who had become the costliest goalkeeper in history when signed from Preston in 1947 (the fee was £7,000!), the defence was the unspectacular part of the side. The forwards were the men to catch the eye and the imagination. With Matthews and Morten- sen in the opposition, public opinion favoured a high-scoring game, with Blackpool slight favourites. They had an omen in that they had beaten Spurs 4-1 at White Hart Lane, where Newcastle, fielding the eleven which later played at Wembley, had been routed 7-0.

In the event, although Milburn's opportunism turned the match, Newcastle's defence did remarkably well. Harvey gave a strong lead, Corbett fared as well against Matthews as any full-back could expect, and Brennan was in superlative form. He held Mortensen far better than Hayward held Milburn: the game hinged on those two individual pairings.

On a perfect spring afternoon, the Final began with a flurry of raids and counter-raids. Slater, hooking a shot on the turn, left Fairbrother helpless, only to see the ball slip past the upright, and Mortensen had a run on the right and a big shot across the goal face. Then Newcastle delivered a punch of their own, a lightning move ending with Milburn putting the ball past Farm - after using a hand to control it. No goal, but proof of menace.

To counter Milburn's speed, Blackpool left their full-backs unusually wide apart, ready to join Hayward in a quick advance. As a result, play was often stopped for offside, and the interruptions added to Newcastle's troubles as they tried to find their touch. They had won only one of their eleven League games since the semi-final, and the edge had gone, if only temporarily, from their attack. So the goals did not come, although Blackpool twice went close after Slater's near miss. First Mortensen headed Perry's corner past Fairbrother, only for Cowell to head off the line, and then Matthews left two men turning the wrong way and put Mudie clear on the right with two men in support, but the Scot's pass was both ill-timed and poorly placed.

United persisted in their efforts to send Milburn through, and still the move was foiled by offside or interception. Yet reliance on the whistle can be a two-edged weapon, as Milburn showed just before the interval, when he held back to take the pass, then turned and raced ahead as the defence hesitated, waiting for a decision which did not come. Milburn covered thirty yards at his fastest speed before unleashing his shot, and only Farm's headlong dive kept him from a goal.

This was a warning, which Blackpool ignored. And they were made to pay, with the second half five minutes old. A Matthews run ended with a pass behind Mortensen, and Robledo moved quickly from defence to send the ball far up the middle. As Milburn set off in pursuit, Hayward and Garrett looked to the linesman for yet another offside signal. Again that signal did not materialize. Milburn was "right", by a fraction, and away he went. In his anxiety the centre-forward might well have put his shot high or wide, or at the advancing goalkeeper. He might have hesitated, to be overhauled by his pursuers. But this was Milburn. Fictional heroes don't miss, and nor did the idol of Newcastle. At just the right moment, with just the right force, to just the right spot - low, inside Farm's right-hand post Milburn calmly sent in his shot. Blackpool's trap had failed, Newcastle were in front, and Milburn had scored in every round of the competition.

Four minutes later the lead was doubled. This time the goal was made and scored in a second, with no long chase while the Stadium held its collective breath, but in its differing way the result was just as spectacular. Walker turned a pass inside to Taylor, who rolled the ball underfoot with his studs, into Milburn's path. Milburn was a long stride outside the penalty area, and at a slight angle, but his immediate left-foot shot was of such power that Farm had no chance of getting across in time as it rose and flashed past him, into his top right-hand corner. It was a magnificent effort, one which brought the scorer a congratulatory handshake from his international colleague, Mortensen. And although thirty-five minutes remained, the task of saving the match was clearly beyond Blackpool's ability.

Not that they caved in. They fought on, taking heart from the example of the ageless wonder on the right wing. Matthews, seeming to scorn the efforts of others, came infield on half a dozen occasions, shaking off the dogged Corbett, and producing a string of shots. But each one either passed wide or cannoned off the covering mass of black and white jerseys. Now Blackpool looked for inspiration from Mortensen, but this was not his day. Every run, every turn, took him up against the implacable bulk of Brennan, six feet two inches of skill and determination, taking giant strides on those size eleven boots.

Right to the end Matthews and Mortensen fought on, with Johnston giving them ample possession and Kelly no less a glutton for work in midfield. But Mudie and Slater were negligible, Perry had faded, and Newcastle's defence, helped by two, three, or even four forwards, stood firm. Indeed, the last word could have been Milburn's. Having scored a goal with each foot, he now missed the chance of a hat-trick when Taylor's cross, which had eluded Farm, skidded from his head across the vacant goal.

No matter: Milburn had done enough. And Matthews was still without that medal.

David Prole from Cup Final Story

1946-1965

Blackpool: Farm, Shimwell, Garrett,

Johnston, Hayward, Kelly, Matthews, Mudie,

Mortensen, WJ Slater, Perry.

Referee: W.Ling of Cambridge.

Goals: Milburn 50,54

Crowd: 100,000